“Working with the material day-to-day, you shape yourself as well.” (Nathanaël Le Berre)

The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree…

The desire to create has been with Nathanaël Le Berre since childhood. The only question was how. He could have worked with pens, leather or ceramics, but he chose metal. This is the medium through which he expresses his vision and from which he shapes his inventive and virtuosic artworks. The eldest of four children, Nathanaël, 40, grew up in the Le Berre family home, in a small village in Burgundy. He was surrounded by art from the moment he was born. His Dutch grandfather, a charismatic designer of historical monuments, introduced him to the sacred art of icons and the secrets of calligraphy.

Nathanaël loved to sneak into the little workshop where his father, an homeopathic practitioner, bound books and fashioned string instruments; he was mesmerised by the meticulousness and dexterity involved. His mother, a great art lover, was particularly fond of drawing. She helped to cultivate his taste. In this family environment, the boy was free to nurture his imagination, an inner world influenced by the religious and the sacred, where the invisible and, at times, the supernatural, take shape.

The medium

At 18, Nathanaël opted for the Ecole Nationale Supérieure d'Art in Dijon, home of plastic artist Orlan. But with subjects like art history and contemporary art, the curriculum was far too abstract and theoretical for a young man who wanted to jump right in and get his hands dirty. He ended up finding his place at the ENSAAMA/Olivier de Serres school of applied art. Given the choice between mosaics and stained glass, he chose the latter.

While it could have been a perfect choice, considering his religious upbringing, he came to feel the need to shake off that influence. He loved drawing, but he wanted to work with shapes and proportions rather than colours. Everything fell into place when he stumbled upon freehand artisanal metalworking at ENSAAMA. “I was fascinated by the idea of shaping a sheet of metal with hammers, of three-dimension creations. I saw untapped potential in the ingenuity of this traditional craft, the opportunity to express a way of thinking.” He enrolled for an artistic profession diploma (DMA) in metal and graduated in 1999.

The method

During his years learning the art of freehand metalwork, Nathanaël met teachers who opened his eyes to the innovative ways in which traditional techniques can be used. One teacher in particular would have a significant impact on him. Hervé Wahlen, a member of the jury during his final assessment, singled him out to work in his workshop. Freshly graduated, Nathanaël was hired by La Licorne, where he made pieces in precious metals for high-end brands. He also worked at Ateliers Bataillard as an artistic ironwork designer, where he studied different styles, refined his tastes, developed an eye for quality and got to know the work of interior designers such as Pierre Yovanovitch, Jean-Louis Deniot, Christian Liaigre and Alberto Pinto.

With Wahlen, Nathanaël furthered his education. He observed his mentor at work, and contributed to his creations. He was able to get up close to the artistic process, before gathering up the courage to forge his own path. “I was still boxed in by the technical aspects of the craft,” he explains. “I didn't dare let go and create more purely artistic shapes. I needed to establish my own style, to make the material my own and really understand it”.

Getting started

When Wahlen moved out of his workshop, a former roman scale factory in Montreuil, just outside Paris, he offered Nathanaël the chance to take it over. This was a great opportunity; Nathanaël was now able to give free reign to his own creativity. With Wahlen's help, he also acquired tools that once belonged to renowned metal worker René Gabriel Lacroix. It was a way to mark the transition; the tools were a connection to the past, and a token of good luck for the future. “The solitude of the workshop afforded me the opportunity to appropriate the craft and produce my own work,” he says. He worked on sheets of steel, a more affordable version of copperware. As early as 2005, his sculptures found a perfect showcase at the Triode gallery, rue de Jacob, in Paris.

In 2008, having left the Ateliers Bataillard in order to concentrate on his art, Nathanaël moved to Janville-sur-Juin, not far from Etampes, where he worked in a former sawmill. Conditions were tough, but the forced isolation enabled him to dig deeper and find fresh inspiration. The monastic-style setting proved fertile ground for his sculptures. “I was finally able to let go, to be at ease with the kind of oblivion required in order to create.” He also discovered 3D modelling, which allowed him to dream up new shapes. (He eventually moved to his current workshop in Aubervilliers, in 2010.)

Collaborations and recognition

In 2009, Christian Liaigre asked Nathanaël to exhibit two of his works, Torse Orange and Torsion, in his gallery. He subsequently placed orders with him for some specific pieces, including reading and suspension lamps. Nathanaël was thus able to enter into the exclusive circle of luxury interior decorators, an experience which, in turn, fed his own personal artistic explorations. His repertoire of shapes grew, along with his self-confidence.

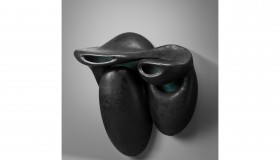

In 2011, he met gallery owner Patrick Fourtin – who exhibited some of his pieces, notably Couleur carbone, Eye Eve and Mallorca – and Parisian gallery owner Michèle Hayem, who encouraged him to move towards larger and more functional works. At her behest, he came up with the shelf-like sculpture La Vague d’encre in 2015, and other pieces.

Wanting to test his work out on industry professionals, Nathanaël entered the Grands Prix de la création de la Ville de Paris competition two years in a row. Around the same time, he entered the exceptional talent section of the prestigious Liliane Bettencourt prize for craftsmanship (“Intelligence de la Main”), which he won the third time around with his sculpture L'infini. Beyond recognition for his masterful use of traditional artisanal techniques, this prize was a tribute to his work, which straddles sculpture and functional art, and to the poetic and benevolent world vision reflected in his art.

Text: Olivier Waché.